An Inside Look at One of the First PCT Thru-Hikes in History: Stolen Packs, Near-Death Experiences, and Life-changing Adventure

Today’s PCT thru-hikers have a wealth of resources at their disposal — trail towns that cater to long-distance hikers, dedicated trail angels, GPS navigation, up-to-date water reports, and an entire community ready to offer support. But what was it like to hike the Pacific Crest Trail when none of that existed? Few people can answer that question firsthand, but Hal Simmons is one of them.

The type of blaze that marked the trail during Hal Simmons’ 1974 thru-hike of the Pacific Crest Trail. Photo: Hal Simmons

Now living in Granby, Colorado — just a short drive from the Continental Divide Trail — Hal became the one of the first people to complete a PCT thru-hike in 1974. While reliable records are scarce, he believes he was either the 10th or 11th person to travel the entirety of the trail, setting out from the Mexican border in early April and reaching Canada in late October.

To hear his story, I made the drive over Berthoud Pass to Granby, where Hal and his wife, Brenda, welcomed me for dinner. Over a home-cooked meal, I asked every question I could think of about his journey. As the evening stretched on, Hal pulled out a box of old slides, and we watched his 1974 adventure unfold one frame at a time.

While the gear looks different, some things clearly haven’t changed about thru-hiking in the past 50 years (sitting and staring at a beautiful view with your shoes off). Photo: Hal Simmons

What I heard was a story of joy, resilience, commitment, and a deep love for the wilderness. From navigating the Sierra with an 80-pound pack and subsisting off food from the land to watching thieves steal all of his gear, Hal’s journey offers a rare glimpse into the trail’s early days.

An Idea Is Born

Hal was taking a National Park Survey class at Colorado State University when he first heard about the 1968 National Trails System Act — the law that officially established America’s 11 National Scenic Trails, including the Appalachian, Continental Divide, and Pacific Crest trails. The idea of walking across an entire landscape captivated him. “I’d like to do that,” he thought.

“I wish I had gotten the person more in focus,” Hal says as we flip through his PCT adventure on film. He then waves away the idea. “I suppose the mountain is the important part.” Photo: Hal Simmons

But why the PCT over the CDT, despite living closer to the Rockies? For Hal, the answer was simple: the Mojave Desert fascinated him, and he wanted to experience it on foot. He was also drawn by the John Muir Trail, which even back then was already famous for its beauty and grandeur.

By the time Hal finished college in 1971, the dream of a thru-hike was still alive — but so was the Vietnam War. He received a draft notice and braced for deployment, only for the call to never come. Then, one day, a new draft card arrived in the mail: the draft had ended, and he wouldn’t have to serve after all. With his future suddenly wide open, Hal took a job at a ranch, spending long days alone, hauling heavy loads, and walking many miles each day. The PCT was never far from his mind.

Preparing for the Hike

A $500 gift from his grandmother, plus his savings from ranch work, gave Hal just enough to start gathering gear. A local outfitter, impressed by his plan, sold him Mountain House meals in bulk at a discount. Hal began packing boxes with gear and food to sustain him along the way, ending up with enough resupply boxes to fill his truck. His father dedicated half of their two-car garage to storing the boxes, promising to mail them to Hal as he hiked.

Planning got easier when Hal found two books: The Pacific Crest Trail Volume 1: California by Thomas Winnett and The Pacific Crest Trail Volume 2: Oregon & Washington by Jeff Schaffer and Bev & Fred Hartline. These gave him a better sense of resupply points, along with pages of maps he would later use to navigate while on the trail. To keep his gear in shape, he visited a local shoe shop and learned how to resole his own hiking boots and purchased a repair kit to fix them himself on the trail.

When the day finally came, his friend Dave Tucker loaded up his pickup truck and drove Hal, his then-girlfriend Denise Myers, and two other friends of theirs to the Mexican border. Of the four, only Hal and Denise would find their way to the Canadian border.

There was no big monument marking the trail’s start — just an unassuming international boundary marker. With very little fanfare, Hal stepped onto the PCT and started heading north. It was 1974, just six years after the PCT was officially designated a National Scenic Trail.

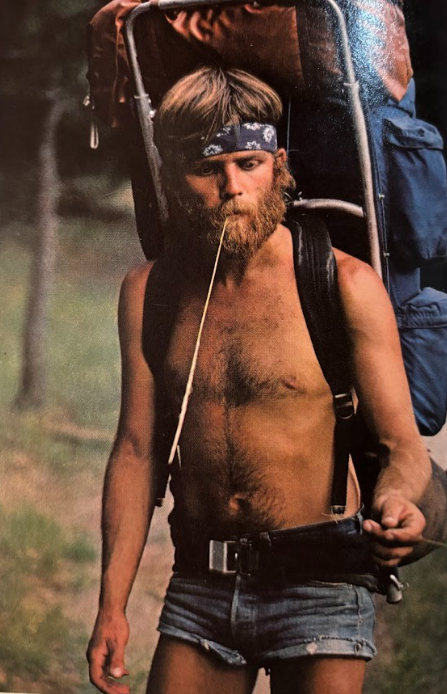

“I was wearing jeans and it was too hot,” Hal says about the desert. He turned his jeans into cutoffs, immediately thinking, “shoot, these are too short! But, I didn’t have any more, so I just got used to them”. Photo: Hal Simmons

Starting Out

While Hal began with a group of four, only three of them made it past the first week. One hiker quickly decided the trail wasn’t for her, saying it simply wasn’t what she had expected. But before setting out, the group had made a pact — if anyone quit, their resupply boxes became fair game.

“It ended up being a blessing,” Hal laughs, admitting they desperately needed the extra food.

From the beginning, Hal settled into a routine: start early, stop early, and keep consistent miles. He averaged 17 miles a day, didn’t carry a tent, and preferred sleeping under the stars. For most of the hike, it never rained enough to make him rethink that decision — until Washington, when it rained for 22 days straight. He finally had his dad mail him a tent.

Camping on the Knife’s Edge Trail in the Goat Rocks Wilderness. He recounts being grateful that no people or animals came across the trail in the night, as there would be nowhere to go but over them. Photo: Hal Simmons

Despite the hardships, he never felt unsafe. Once, in what Hal describes as his “on-trail miracle,” he was hiking below his group when they dislodged a boulder the size of a school bus. Frozen in place and unsure of which way to move, he watched as it barreled straight toward him. Just before crashing into him, the rock split cleanly in two—each half passing by Hal on either side.

“I felt like I had an angel with me the whole time,” he says.

Entering the Sierra

Hal’s journey took a dramatic turn as he entered the Sierra, where the trail began to test him in ways he had never imagined. After leaving Weldon, the group faced what Hal calls the toughest climb of the entire hike. With an expected 22 days to the next resupply, they found themselves slogging up a merciless climb with 80-pound packs on their backs. They had expected plentiful water from the Sierra snowmelt but instead found only dry trail. They were thirsty, tired, and hiking well into the night, listening for any sign of running water.

Entering sustained snowpack. Hal remembers how incredible it was to go from the desert to the mountains over the course of one climb. Photo: Hal Simmons

Hours after sunset, as exhaustion set in, Hal remembers feeling intense relief at the sound of flowing water. They scrambled down off-trail to reach the small stream and chugged as much water as they could.

“It was lumpy, but we didn’t mind,” Hal says. “But, then, we heard the mooing.”

Without filters, there was no way to avoid the cow poop in the water that they were so desperate to drink. Luckily, none of them got sick.

Finding Food

It wasn’t just a lack of reliable information surrounding water sources that made the trail more difficult — food was also hard to come by. Unlike today, most people Hal encountered in towns along the trail had no idea what the PCT was, much less that people would choose to hike the whole thing in one shot. Without the ability to rely on consistent hitches, trail magic, or even nearby towns having grocery stores, Hal often had to get creative to find food.

He had brought a fishing rod, hoping to catch meals along the way, but calories were always in short supply. Between the Mexican border and Tuolumne Meadows, he lost 23 pounds, dropping from 165 to 142 pounds.

He recounts the story of his greatest fishing success in the Sierra at Rae Lakes. In a single evening, Hal and two friends caught, cooked, and ate 34 trout. The group had no fishing permits, and Hal says a ranger walked up minutes after they had packed up their supplies and finished their final fish.

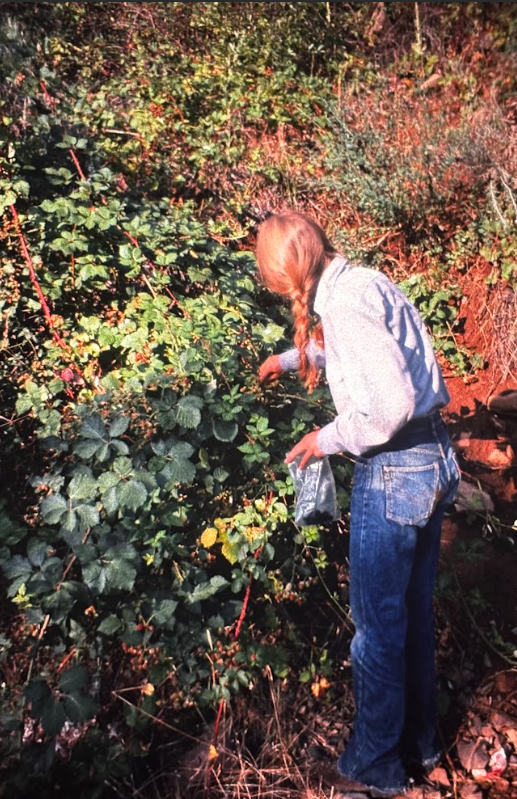

Outside of fishing, Hal says he ate a lot of wild onions and berries scavenged from the sides of the trail. Over Brenda’s peach and raspberry cobbler, Hal entertains us with stories about thimbleberries, salmonberries, and “blackberries as large as your thumb.” Without the heavy foot traffic the PCT sees nowadays, Hal’s only competition for these berries was the bears.

Hal and I compared photos, and loved when we would have pictures from the same spots. We both have identical images of the spires while ascending Mount Whitney. Photo: Hal Simmons

Hal shares a story from a later adventure in Banff National Park, when he and his group collected an entire Ziploc bag full of a berry they couldn’t identify. Unable to reach a consensus on whether to risk eating the mystery berries, they decided to leave the bag overnight and put off the decision until morning. That night, strange noises woke Hal. Peering outside, he watched as a massive grizzly bear sat just feet from his tent, casually eating every last one of their berries.

A Lack of Infrastructure

In 1974, river crossings weren’t a matter of following a marked trail to a sturdy footbridge. Most of the time, there were no bridges at all. The only way across was to find a fallen tree or wade through ice-cold, rushing water. Sometimes, the process of finding a safe crossing took hours.

One of the hikers Hal started the trail with, Robert Clancey, had worked as a structural steel iron worker, balancing on beams hundreds of feet in the air. He taught Hal to use a long stick, like a tightrope walker’s pole, to steady himself as he shuffled across logs above the rapids. For the most dangerous crossings, Hal opted for a safer method: sitting down and scooting across.

At Woods Creek, he and his group encountered a hiker attempting to cross. The man took off his boots and threw them across — only one made it to the other side. He had no choice but to hike to the next town with one boot and one down bootie. To make matters worse, Hal tells us, the man was subsisting on a diet of cat food and oats, and had completely depleted his supply of toilet paper. “He was on a budget,” Hal explains, assuring me that the cat food was “human grade.”

By that time, Hal’s group had also run out of food, so they struck a deal — one roll of toilet paper for ten pounds of oats. Modern thru-hikers might cringe at surviving on nothing but oats, but Hal and his friends ate every last bite by the following night.

“After that,” Hal laughs, “we needed the toilet paper.”

Pack Theft

When asked about the most frustrating moment he had to overcome, Hal recounts watching his pack get stolen in Southern California. Just outside of Wrightwood, he and his friends left their packs by the roadside to climb a short hill for some shade. As they ate lunch, they heard a car pull up — and turned just in time to witness someone loading their packs into the car and speeding away.

With no gear and few options, Hal reported the theft to the police, called his sister, and waited. His sister emptied her savings account to buy him a new pack and mailed him her sleeping bag, sleeping pad, and a camera. It took four months before he was reunited with his original pack, despite clearly seeing the car’s license plate (a sequence he still has memorized to this day!).

In the meantime, after receiving the package from his sister in Wrightwood, he hiked on. As with so many of Hal’s stories, this part of the journey was never defined by the setbacks. Instead, Hal accepted the inevitability of needing to press forward, no matter the challenges faced. It’s incredibly inspiring to sit at the dinner table, hearing Hal describe, with the same zenlike calm with which he approaches the rest of his life, moments on the trail that would have sent me into a full-blown meltdown.

Hal reaches the Northern terminus. This photo now hangs in his and Brenda’s house. Photo: Hal Simmons

From Hal, there is never a hint of ego over how much harder it must have been to thru-hike in 1974. There are no comparisons, judgement, or dismissals of current thru-hikers’ experiences (although he does marvel at how small modern hikers’ backpacks are). Instead, he just delights in telling the story of the hike that changed his life and put him on the path to where he is today.

Life After Trail

Growing up, Hal’s dad often asked him why he never finished the things he started. When he set out on the PCT, he had one expectation for himself: to finish—not for anyone else, but to prove to himself that he could. When I asked if he ever thought about quitting, he didn’t hesitate. “I never once thought about quitting because I always wanted to see what was next. I had no idea what was ahead of me.”

Hal and friends at the summit of Mount Whitney (we think— some of the slides have gotten out of order throughout the years). Photo: Hal Simmons

Both Hal and Brenda credit the PCT with teaching him the grit to see things through. That persistence carried over into the construction business he would go on to run after the trail.

Sitting in their beautiful home — one that Hal built himself — surrounded by the Simmons’ warmth and kindness, it’s easy to see how those lessons shaped their lives. The adventure didn’t end when he reached the Canadian border. From a float trip down the Yukon River to children named after their favorite hikes and landmarks and a fridge covered in photos of their grandchildren, they’ve built a life filled with exploration, resilience, and joy.

I have no doubt there were grueling moments on the PCT that Hal chose not to dwell on. He’s not one to linger on hardship. Instead, when he looks back on the experience, he remembers the friendships, the deep connection with nature, and the freedom of walking through untouched wilderness.

“It was a piece of cake,” he tells me with a grin. “It just took a long time to eat it.”

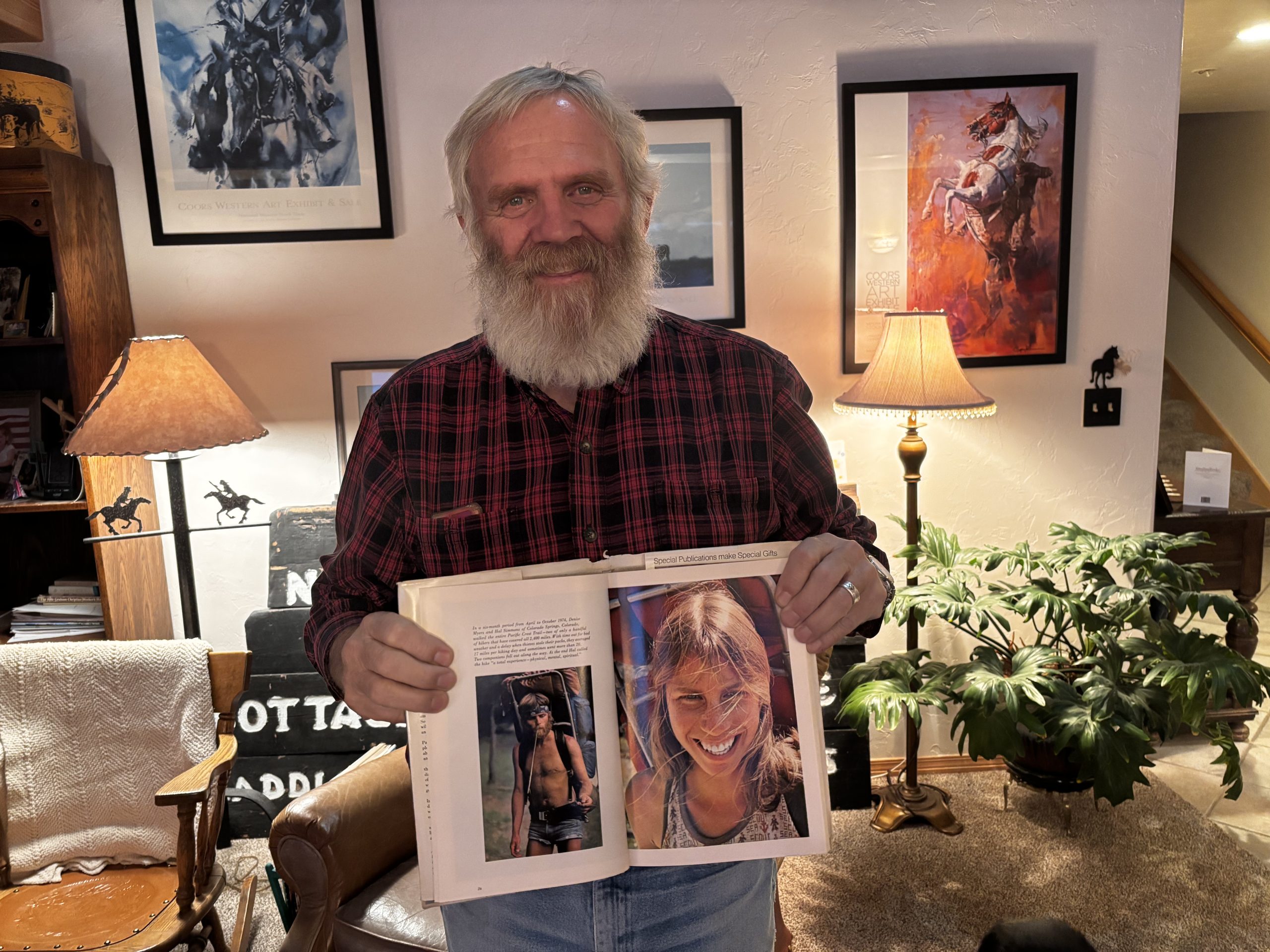

Hal Simmons poses with his photo in the book The Pacific Crest Trail by William R. Gray and photographed by Sam Abell with the National Geographic Society. The book, written in 1974, showcases the trail at the time and includes stories from Hal, Denise Myers (right), and a few others traveling along the trail that year.

Featured image: Hal Simmons

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

">

">

Comments 16

Great story!

I met Hal and stayed with him when I did the CDT in 1977. I did the PCT in 1972, so we had a lot to talk about. David Odell AT71 PCT72 CDT77

I stayed with Hal on the CDT in 2024! He’s still impacting trail communities all this time later. I can’t imagine how wonderful your trail journeys have been. He mentioned you, I’m fairly sure, when we talked. At least, he brought up connecting with another PCT OGer as they completed their triple crown; I can’t imagine that description fits many others!

Good to hear from you Katie. If you are interested you can find the journals from all my hikes at: trailjournals.com/daveodell. Pretty basic stuff, but will give you an idea what it was like to do the trails back in the 70’s.

Definitely going to check out your trail journals!

Thank you so much! I appreciate that

What happened to Denise?

She finished the trail with Hal! Funny enough, she struck up with the Nat Geo photographer along the way, and the two of them married shortly after. Hal and the two of them texted a few weeks ago to celebrate 50 years since the adventure that changed all of their lives.

Absolutely the best story I’ve read in a while, thanks for writing it.

That really means a lot to me, thank you!

Thank you so very much for introducing me to one of the “OG” thru-hikers of this trail. It seems that I often hear about the early AT hikers, but very seldom do I hear about the early hikers of the other Triple Crown trails.

And there’s so little information out there! The history is so rich and so unknown.

Wow! This was really an enjoyable story. I appreciate the fact that you had to be tough as nails to get through this in the early days. Not that it is easy now, but this was really inspirational. Well written!

Great story!!!

Thank you for this! It would be awesome to hear more stories like this about the OGers 🤩

After spending many years doing trail work on the PCT, I’m most curious as to how you found your way, especially over areas covered with snow. It must have all been map and compass and word of mouth. Dennis