I Thru-Hiked the PCT in the Snowiest Year on Record: Here’s What You Need to Know About Navigating PCT Snow

There’s always a good amount of fear mongering when it comes to navigating early-season snow on the PCT, but a continuous thru-hike is possible even in the snowiest conditions if you’re prepared and cautious. I should know: I was among the two percent of hikers who completed a continuous northbound thru-hike of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) in 2023, a year that saw historic snowfall in the Sierra.

The things I expected to be challenging turned out to be minor compared to what I learned while trekking through 500 miles of snow during my thru-hike.

I had completed the Appalachian Trail in 2022 and was no stranger to long-distance hiking by the time I committed to thru-hiking the PCT in 2023. But as reports of record-breaking snow in California made their way into the news, I found myself growing nervous about my impending April 5th start date.

By March, Mammoth Mountain, CA, was reporting 900 inches of total snowfall on the summit, the highest snowfall on record, and I knew there was no way it would all be melted by the time I reached the Sierra in June. There would be no trail to follow, and I’d have to rely on navigation skills to make my way north.

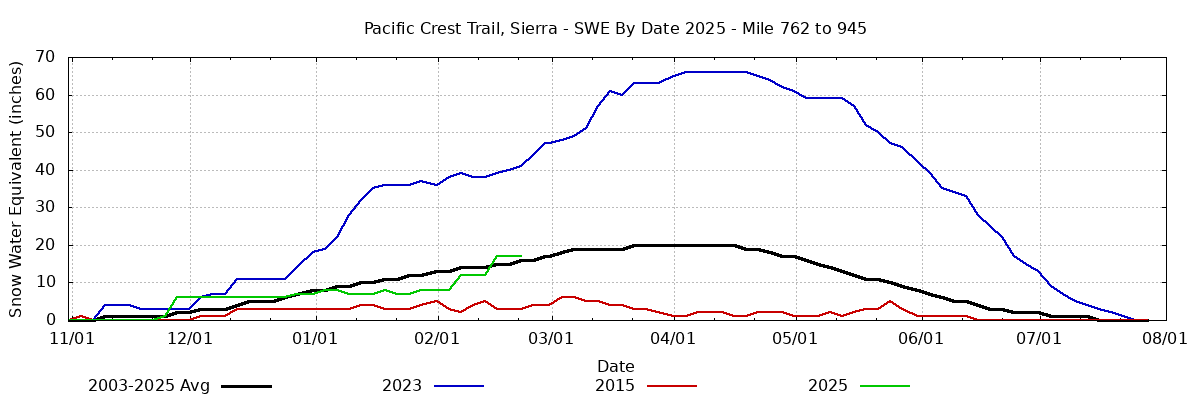

According to Postholer, trail snow in the Sierra is currently 107% of average for this date, so right on track. Contrast this with 2023, the year I thru-hiked, when trail snow depth shattered records.

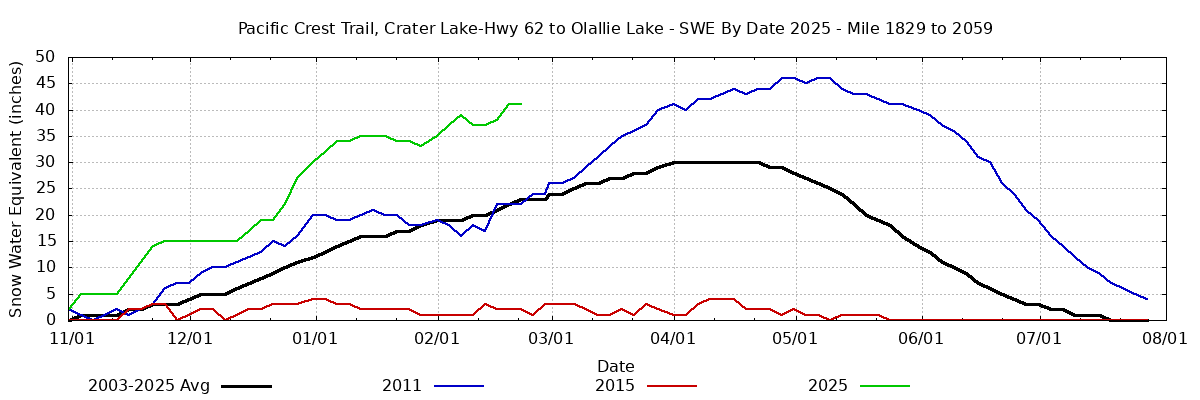

Meanwhile, trail snow in Oregon is currently above average for this date. March and even April snowstorms can still dramatically change snowpack, so take these charts with a grain of salt and continue to monitor conditions throughout the spring. Chart: Postholer

“Many said the high mountain passes would be impassable, and even more said a thru-hike would be impossible.”

(For reference to anyone planning a thru-hike in 2025, as of February 2025 the current snowfall total for Mammoth is 130 inches. The average total snowfall is about 400 inches per year. Crater Lake, OR is reporting 132 inches of current snowfall, which is above average for this time of year but well within the average reported snowfall total of 575 inches per year.)

Hiking forums were abuzz with warnings about deadly river crossings and drowning potential. Many said the high mountain passes would be impassable, and even more said a thru-hike would be impossible.

Having grown up in New Hampshire spending winters hiking in the White Mountains, I had more snow hiking experience than most of my fellow thru-hikers, but I could not help but feel unsure of what lay ahead. My partner, Tiga, and I had many discussions about the record snowfall situation and whether hiking the CDT would be a better option. I knew I didn’t want to flip or skip miles, so if I was going to change course, it would have to be before starting the trail.

Ultimately, we decided to go ahead with our plan to hike the PCT. Using caution and common sense, this was going to be the time to put my knowledge to the test.

Entering the Snow

I reached the end of the southern desert portion of the PCT at Kennedy Meadows South (KMS) on May 19th. It was here that every thru-hiker had to decide, once and for all, how they would handle the record-high snowpack that awaited them in the Sierra. Most hikers decided to skip the snowy sections altogether, either out of fear or inexperience. Others scrambled to find partners or join groups who were willing to give the snow a try.

Most who set out to attempt the Sierra exited at Lone Pine, the first bailout point, a mere 43 miles north of KMS. It was clear that maintaining a continuous northbound path through the Sierra would be a major challenge this year.

A Note on Group Size

Having a buddy system for climbing high mountain passes, crossing snow bridges and fording rivers is a sound plan. Many had no experience in the snow and decided on a safety-in-numbers strategy, assembling groups of eight or more hikers. While having a partner is always a good choice for decision-making and safety, I would caution against forming too large of a group.

The larger the group, the harder it is to agree on things like wake-up times, hiking pace, rest breaks, resupply points, and varying comfort levels with snow and navigating terrain. For the most part, the smaller groups of two to four hikers were the most successful, in my observation.

Resupply and Bailout Strategy for the Sierra in High Snow

I was fortunate to have Tiga, whom I had hiked the entire AT with, and another friend (Casper) who we met very early on the PCT. The three of us had varying degrees of snow experience but decided that we would stick together and rely on each other.

We agreed on bailout points, checked weather forecasts, and continued our wintry expedition north. We planned resupplies from Kearsarge Pass (87 miles), Bishop Pass (43 miles), Mammoth Pass (75 miles), Sonora Pass (110 miles), Tahoe (75 miles), and Sierra City (103 miles). Each time we exited, we adjusted gear, food, and gave ourselves time to rest in town.

At one point, we were attempting to rejoin the PCT at Bishop Pass when a major storm system moved in, bringing a snow and lightning storm that forced us to reverse course. It was expected to storm on and off for the next several days. We took inventory of our supplies and decided that we would not have enough food to make it to Mammoth if we were slowed down significantly by fresh snowfall or if we were trapped in our tents waiting out the weather.

Almost at the top of the pass, we turned around, descended all the way back to Bishop, and ended up taking an impromptu road trip to the California coast for five days to wait out the snow. It turned out to be one of our best decisions; several hikers we knew who were behind us or just ahead of us on trail had harrowing stories about being trapped in their tents for days, enduring frigid temperatuers and high wind while their food supplies dwindled. Many were understandably shaken up by the experience and skipped the remaining snow from there.

It’s always a difficult decision to turn back, but keeping your ego in check and doing what’s best for the safety of everyone in the group is imperative. After our side quest, we returned to the trail re-energized with fresh legs and sunny skies and continued north, and it was relatively smooth sailing from there.

Gear Considerations for Hiking the Sierra in High Snow

Tent: Tiga and I put a lot of thought into which tent we would carry through the Sierra. We had started the trail with the Durston X-Mid 2 UL tent, which was great in the desert, but for several reasons, we decided to switch back to the Zpacks Duplex that we had carried on the AT. The footprint of the Zpacks is much smaller, helpful since often we would find small patches of dry ground or exposed granite to set up on. More importantly, the freestanding Flex Kit made setting up in the snow a breeze.

Sleeping bag: I switched from a 40-degree bag to a 20-degree Feather Friends sleeping bags that kept me sufficiently warm at night when the temperatures plummeted at elevation after the sun went down.

Footwear: I switched from trail runners to Lowa Renegade boots to hike the nearly 500 miles through the Sierra. My feet were significantly warmer and in better condition than those who stayed in trail runners. Additionally, crampons and microspikes are more compatible with boots.

Bear canister: Bear canisters are required in the Sierra. We had to carry them for over 400 miles to South Lake Tahoe. They added weight and were awkward to carry. On top of that, it was impossible to fit seven to eight days’ worth of food in one. I had no choice but to carry an additional food bag, defeating the purpose of the bear canister altogether.

Snowshoes (no): I carried snowshoes for the initial 90 miles to our first exit point to resupply at Kearsarge Pass. Although they were helpful when the afternoon sun turned the snow to mush, I decided that carrying less weight and starting our days at 2-3am when the snow was consolidated was a better strategy. I sent them home.

With all the equipment swaps, the addition of snow gear such as ice axes and crampons, and the weight of extra food, my pack nearly doubled in weight when I entered the Sierra. Normally, my base weight is around 12 pounds and total pack weight is around 20 with a few days of food and water. I left KMS with nearly 40 pounds on my back, which slowed my pace significantly.

Navigating the PCT in a High-Snow Year

Most thru-hikers can follow established trails in summertime conditions, but many lack proper navigation skills and underestimate the importance of reading maps. With modern technology, many have come to rely solely on cellular devices and apps like FarOut or Gaia for route finding, not considering what might happen if their batteries die or their technology otherwise fails.

Reading topography, determining direction of travel, and understanding scale are critically important skills for successful snow travel. I can’t overstate the vastness and expansiveness of the Sierra Nevada when the trail is buried under 40 feet of snow. The trail was nonexistent, blazes and cairns were buried, and avalanches had decimated entire stands of trees, reshaping the landscape. To be successful in a high snow year, I can’t overstate the importance of map studying and being able to read topography.

After departing KMS, we quickly lost the trail in deep snow and leaned into navigation skills to continue our trek. There were only a handful of people ahead of us; following their tracks often led us off trail, and frequently to precarious places. Orienteering was of the utmost importance. For safety, I carried a Garmin inReach and used it on occasion to check in with my point of contact and get the most updated weather forecasts, another useful tool for sound decision making.

Some of the Biggest Snow-Related Challenges I Faced on the PCT

Sunburn: Entering the Sierra and being exposed to snow glare, I sunburned places I didn’t think possible, including the insides of my nostrils, the inside of my lower lip, my eyeballs, and my tongue. Snow is more reflective than water and can reflect up to 90% of UV light on a sunny day. I was fortunate to avoid snow blindness, a type of eye damage caused by reflected UV light, but after a grueling section of trail between KMS and our first resupply point at Kearsarge Pass, I went back in better prepared with sun protection; this included wrap around glacier glasses, high quality sunscreen, and a buff to cover the lower part of my face.

Postholing: Postholes were treacherous, and the ones in the Sierra, particularly in avalanche areas, were especially challenging. There’s nothing worse than suddenly and unexpectedly plunging knee-, thigh-, or chest-deep into snow and struggling to get out. At one point just outside Yosemite, Tiga plunged chest-deep into one. The only thing holding him above ground was his pack.

We learned to avoid the worst of the postholes by hiking most of our miles in the early morning when the snow was consolidated and stable. Alpine starts (waking up at 2-3 a.m. to get a jump on melting snow) became the norm.

Sun Cups: Sun cups sound sweet, but these little ankle twisters were the bane of my existence. Sun cups are bowl shaped depressions in the melting and refreezing snow. They resemble honeycomb or egg carton patterns, with sharp ridges that separate hollows anywhere from a few inches to over a foot deep.

In the early mornings, the jagged edges were more stable, but by midday they softened and became more slippery, deteriorating into yet more treacherous obstacles. I slipped and fell on them more times than I could count. They were easier to navigate when frozen, so again, we leaned into alpine starts.

Tree Wells: Hailing from the east coast, I had never experienced tree wells. Tree wells are deep depressions around the bases of trees; as snow consolidates in the springtime, they essentially become snow holes, some as deep as 10-12 feet. They make navigating dense forests difficult, as you risk slipping and falling into them (hopefully without injuring yourself on the way down) and then having to exert energy to climb back out.

The only time I appreciated tree wells was when one caught my bear canister after it launched off my pack, saving me from a long walk downhill to retrieve it.

Avalanche Areas: Avalanche debris left some parts of the trail buried and challenging to navigate. My legs were covered in scrapes and bruises from climbing through, over, or around these messes. Also, the worst postholes tended to occur near down trees or large boulders and rocks that were buried under the snow, making recently avalanched areas even more treacherous to navigate. We learned to avoid these areas as much as possible.

Road Walks: Long road walks added mileage and elevation to and from towns to resupply on top of already tired legs from slogging through the snow. Most of the roads that hikers typically hitch from were still closed, gated, and unplowed. I had to account for additional mileage and time when planning resupply points, and I carried extra food to accommodate the extra miles.

Alpine Starts: Waking up in the middle of the night to get miles in and climb passes before the snow turned to mashed potatoes left me physically exhausted. These early mornings were a necessity, but they weren’t easy. Packing frozen gear was miserable, and each morning I walked on snow by headlamp for miles before the sun would rise and warm me up.

Snow Bridges and Water Crossings: While much of the initial fear mongering focused on deadly river crossings, in reality there was so much snow that we primarily used snow bridges to cross rivers.

Much of the dissuasion surrounding water crossings was directed towards women with smaller statures. This stemmed from 2017, when two women, each thru-hiking the PCT alone, attempted river crossings and drowned. I never doubted the strength or ability of any of the women I met in the Sierra.

In 2023, the melting snow resulted in rapid currents and high-water levels, but my group would take extra time to walk up and down the creeks to look for suitable, safe snow bridges to cross. I used downed trees and sometimes rocks if I could not find a suitable snow bridge, and a handful of times, we scouted out safe places to wade across rivers. We would look for wider points in the river with slower currents and be sure to cross close together to ensure we all made it safely to the other side.

At no point did I find any river on the PCT uncrossable.

Frozen Boots: I could have done without the uncomfortable morning ritual of cramming my feet into cold, frozen-solid boots at 3 a.m. to start hiking on consolidated snow, but if we didn’t start early, the snow would degrade into slush, which would mean incredibly slow going. If the boots weren’t frozen, they were wet. I accidentally melted them while drying them out on a campfire in one of the final snowy stretches of the trail. I took this as a sign that it was time to switch back to trail runners.

Extra Food Weight: Every thru-hiker knows that food is heavy, but we realized soon after entering the Sierra that we were not carrying enough food to make up for the extra calories we were burning trudging through the snow and trying to stay warm. I remember being hungrier that I’ve ever been after we summited Whitney, but I was rationing what food I had left so I wouldn’t run out before my next resupply point. When I got to Bishop, I ended up getting rid of some gear to make room for more food.

Social Isolation: The most unexpectedly challenging part of the Sierra for me was the social isolation. Our group would hike days upon days without seeing or interacting with anyone.

During the COVID pandemic, I realized how bad I am at social isolating, and I was no better at it in the wilderness. Aside from my two companions, the trail felt downright lonely at times. There was literally no one out in the backcountry except the skeleton crew of hikers who didn’t flip or skip the Sierra, and going four or five days without seeing another soul became the norm. There were no park rangers, no day hikers, no southbound JMT hikers; in fact, most of Yosemite was still inaccessible by road when we passed through. It gave full-on zombie apocalypse vibes.

I recognize the uniqueness of having 25,000 square miles of wilderness to ourselves, but so much of thru-hiking is about the community and finding joy in shared experiences. In the end, the hikers who became our closest friends on the PCT were the other diehards with whom we shared the experience of the Sierra in the highest snow year on record.

Reaching Dry Ground

We reached Truckee on July 4th, and for the most part, had reached the point where we were out of the white stuff. Reflecting on what made the Sierra so difficult, I appreciate that it wasn’t simply the snow, river crossings, or high elevation passes.

Hiking through 500 miles of snow took a lot of grit and mental fortitude. It was not easy, and there were moments where I was either close to tears, cursing the trail, or merely frustrated by the many snow-related obstacles that slowed our progress. But I never wanted to quit.

Growth often demands physical and mental challenges. It pushes us out of our comfort zones and forces us to adapt to new situations, deepen existing skills and embrace uncertainty.

The summer of endless winter has become one of the most unforgettable experiences of my life and one of my proudest accomplishments. Undoubtedly, someday there will again be record snowfall in the Sierra, but with the right gear, preparation, and the ability to take calculated risks, a continuous thru-hike is entirely possible.

Featured image: Photo via Shelly Estabrooks. Graphic design by Zack Goldmann

This website contains affiliate links, which means The Trek may receive a percentage of any product or service you purchase using the links in the articles or advertisements. The buyer pays the same price as they would otherwise, and your purchase helps to support The Trek's ongoing goal to serve you quality backpacking advice and information. Thanks for your support!

To learn more, please visit the About This Site page.

">

">

Comments 12

Such great information!! Sounds like it was a unique and epic experience

So awesome and so proud of you!!!!! Amazing!!!!!!!

SO incredible

So well written by such an accomplished hiker. HB is a certified BA.

My amazing daughter!!!

So proud of you Hummingbird!

Great write up! ❤️

What a fantastic accomplishment, congrats! I hiked the JMT in 2021, but it was a low snow year, so it was a totally different (and much easier) experience. Does Tiga have legs like tree trunks a background in physical therapy and sports injuries? If so, I met him on the Colorado Trail last year and he taped my ankle in Lake City. I had a tendon injury, and Tiga’s taping job enabled me to finish the last 130 miles.

lol yes, that’s me! I’m happy to hear you were able to finish the trail!!!

Hey Hummingbird! I loved reading this! This was my favorite part: “I recognize the uniqueness of having 25,000 square miles of wilderness to ourselves, but so much of thru-hiking is about the community and finding joy in shared experiences. In the end, the hikers who became our closest friends on the PCT were the other diehards with whom we shared the experience of the Sierra in the highest snow year on record.” It was so hard, but I’m so glad that I experienced this challenge.

This is a reply to Tiga:

Wow, it’s a small world! When I was coming down to Spring Creek Pass on the CT, my ankle was killing me and I couldn’t see how I’d be able to complete the trail. Then I was fortunate enough to run into you at the Hiker Center in Lake City, and you were kind enough to tape my ankle. It felt so much better after that and I had so much more confidence walking. I bought some KT Tape and re-taped the ankle (not as professionally as you did) at Molas Pass, and I made it to Durango a few days later. Thanks again for your expertise and for taking the time to help me out!

So many Trek articles are written by people with inflated egos boasting about how tough and special they are. Anyone can hike in a bunch of snow. Why would you want to though? To be the special one? You are so special and unique and tough and wonderful and inspiring and intelligent. There is no one like you. You are amazing.

Shelly, what a truly amazing story of a truly amazing person! You gave reality to my imagination on how grueling that hike was, and how tough and persevering one had to be to complete it. And how prepared and self aware of your skill and ability! I was 75 when I thru hike the JMT in September 2023. I was blessed to get my Aug 31 start. From March until my start date, I scoured the JMT and PCT social sites and read about the disappointment of JMT folks who were giving up their early season start permits (June, July and into early August), and the PCTers who were agonizing over the decisions to by-pass, go so far and exit, or push on through. My hike was amazing, physically challenging and in some places technically challenging for me. And uncrowded! About the only other hikers I encountered, were those PCTers who had flipped and were coming back to the Sierra to complete their adventure. God bless your next adventure!

I hiked the PCT in 2011, which was another big snow year. Most of this resonates with my experience.

I switched to boots, too, but was so glad to get my trail runners back, even though I wasn’t out of the snow yet (it was significant up to Sierra City). I found gore-tex leather boots didn’t keep me drier or warmer after a full day on the snow. They were wet and heavy and froze overnight (as described).

After a couple of days getting used to walking on snow, I found the passes easier than when I’ve done them in other seasons – walk straight up, boot ski down – except for one treacherous icy section of Forester Pass.

In hindsight, I would have entered the Sierra earlier. I loligagged with the super fun Team No Babies until June 15 in hopes that the snow would clear, but that meant the snow bridges had mostly melted and the rivers were fierce and sometimes scary to cross.

I agree with Hummingbird about group size. I left TNB after a few frustrating discussions about navigation, and ended up hiking alone for a few days before catching up with a smaller group. Those days alone in the snow were enchanted, but made for a couple of creek crossings that were unnecessarily risky.

As the climate changes, successful through hikes will be more and more about hikers adapting and less about having the “right” weather.